Some may wonder at the fact that during such a long voyage I was never overcome by sleep. But sleep is nothing more than the product of the soft exhalation of the meats that evaporate from the stomach to the brain, through which Nature feels a need to tie down our souls in order to repair, during the night, all of the vital spirits that the work of the day has consumed. Thus since I didn't eat, I had no need of sleep, and the Sun lent me more essential heat than I lost. Nonetheless as I continued to rise and as I approached the flaming world I felt a certain joy flow into my blood, which rebalanced it and passed into my soul. From time to time I looked up and admired the lively nuances of light which shone into the little crystal dome of my box. I still remember how I directed my eyes into the mouth of the vase when I suddenly felt something heavy flying away from the various parts of my body. A heavy whirlwind of smoke came to suffocate my little lens in shadows, and when I sought to stand up to inspect this blackness in which I was enveloped, I could see neither the vase, nor the mirrors, nor the glass work, nor the cover to my box. I looked down to see what it was that was threatening my little masterpiece, but I could not locate it and could see only the sky all around me. What terrified me even more was to feel, as if the wind had become petrified, some invisible obstacle which was pushing my arms down as I tried to extend them. Suddenly it occurred to me that through my rising I had come up against the firmament which certain philosophers and some astronomers have thought to be solid. I began to fear that I might be caught up by it. Yet the horror which overtook me by the strangeness of this development increased still more at what followed. For as my gaze wandered here and there it fell by chance on my own chest and instead of stopping at the surface of my skin it passed right through me. Then a moment later I realized that I was looking behind myself. As if my body were now nothing more than an organ of sight I felt my flesh, which had lost its opacity, transfer objects directly to my eyes and my eyes brought objects into my flesh. Finally after having bumped myself a thousand times on the arch at the top of my box without having seen it, I concluded that by some secret necessity of light at its source, we had all become transparent. It is not that I couldn?t see the light, since one can see glass, crystal and diamonds, which are all diaphanous, but I imagine that the Sun, in a region very near to it, purges all bodies of their opacity more perfectly than elsewhere, arranging more directly the imperceptible spaces within matter than it does in our world, where its force, after such a long journey, is lessened and can barely lend itself to precious stones. Still, because of the internal equality of their surfaces it bounces off of their various faces, as if through little eyes, so that the green of emeralds or the scarlet of rubies or the violet of amethysts are able to rejuvenate the reflections of this weakened light.

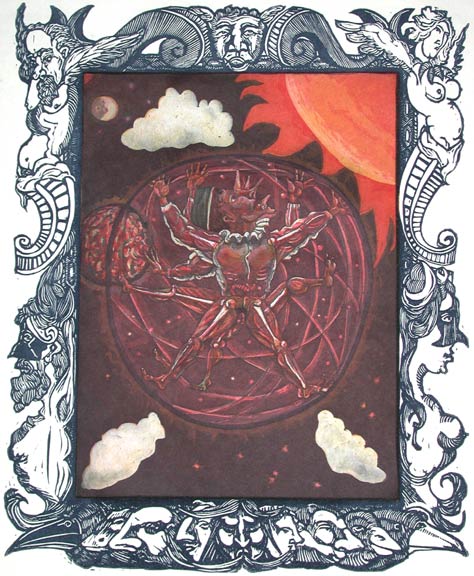

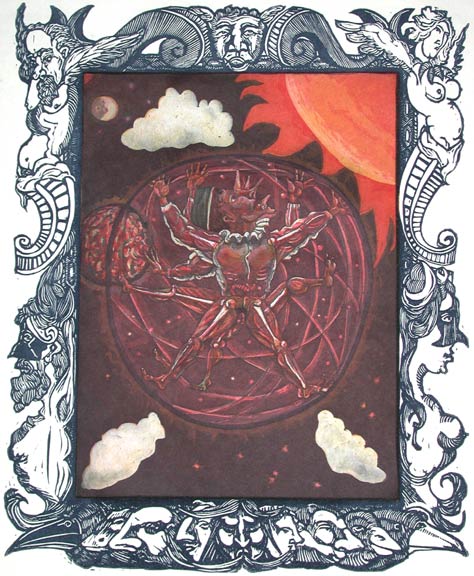

One difficulty may bother the reader here. That is to know how I could see myself and not see my seat, since we had both become diaphanous. I respond that doubtless the Sun acts differently on living bodies than it does on inanimate ones, since no part of my body, neither my skin, nor my bones, nor my entrails, although transparent, had lost its natural color. On the contrary, my lungs kept their soft delicacy beneath a reddish hue. My heart was still bright red and balanced easily between the systole and the diastole. My liver seemed to burn in a fiery purple, cooking the air I breathed, and yet maintained the circulation of blood. In short, I saw myself, I touched myself, I felt the same, and yet I was no more.