Panel Discussion: Against The Grain - Art and Activism:

Thursday, January 27, 7:00 - 9:00 p.m. Lincoln Cushing, Jon Fromer,

Mark Dean Johnson and Pele DeLappe: moderated by Art Hazelwood.

Daughters of the Artists Present: An informal presentation with

Leslie Correll and Nancy and Georgia Rowe.

Followed by labor and activist documentary film screenings. Saturday, February 12, 4:00 p.m.

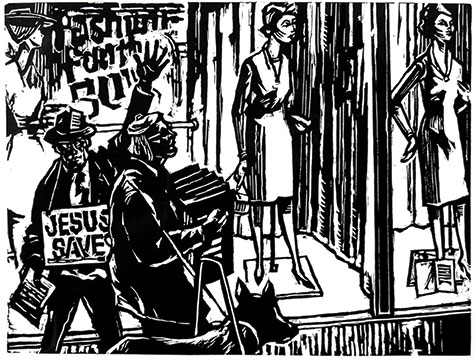

Frank A. Rowe (1921-1985), Market Street, 1952, linocut, 9 x 11 3/4”, Courtesy of the Frank A. Rowe Family Estate

The social ferment, persecutions and upheavals of the twentieth century come into clear focus in the work of Richard Correll (1904-1990) and Frank Rowe (1921-1985), two artists who portrayed their times with personal courage and political conviction despite America’s mid-century turn toward formalist abstraction in art. Encompassing the six decades from the Great Depression through World War II, McCarthyism, the Vietnam War, the Black Power movement, to the Reagan era, their art stands as a testament to the political struggle against oppression and fear that continues up to our own times. Correll and Rowe spent numberless hours serving progressive causes through their hard-hitting political art, whether in fine art prints and paintings, or issue-oriented posters, banners, and magazine illustrations. While both of these artists explored a full range of artistic expression this exhibition focuses on the political side of their work through a selection of more than fifty prints, drawings and paintings from the estates of the artists, who were friends and colleagues at San Francisco’s Graphic Arts Workshop.

Correll began making art in the years following World War I, his pictorial skill and political savvy evident even in his earliest work for The New Masses and other progressive newspapers in Seattle, Washington. During the Depression he became part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the famous federal program that paid artists a modest stipend to create public art. Correll’s prints and murals of the 1930s exalted the natural world and the world of work alike, with strong abstract compositions full of movement and rhythm; the themes combine memorably in his woodcuts on the Pacific Northwest folk hero Paul Bunyan. Correll said of his work, “In art I am chiefly attracted by the synthesis of realism and design; that is, a humanitarian realism and an abstract-dramatic design - each one to augment the other - an old combination of limitless possibilities.”

After World War II, and eleven years in the graphic industry in New York City, Correll moved to San Francisco and began his long association with the Graphic Arts Workshop, a cooperative print studio, which grew out of the San Francisco Labor School after it was closed by McCarthy era pressures. The linocuts and woodcuts that he continued to make for forty more years reflect his sympathy with organized labor, his dismay at the devastations of poverty, racism, industrialization and war with a power and determination surprising in such a gentle soul.

Frank Rowe’s life and art were shaped by the war and its aftermath. A decorated combat paratrooper in World War II, Rowe painted grim images treating his experiences at the D-Day Normandy invasion and the later Battle of the Bulge. These battles, now regarded with such patriotic awe, are treated by Rowe with directness, sincerity and artistic rigor. He portrayed war stripped of its illusion of glamor.

A second disillusionment awaited Rowe in a postwar America grown paranoid under the Red Scare. California’s 1950 Levering Act required a loyalty oath of all state employees, including Rowe, then an art teacher at San Francisco State University. His adamant refusal to comply led to his firing and to years of government harassment before the law was invalidated as unconstitutional in 1967. It also shaped his art, his prints and paintings commenting wittily and passionately on the Korean War (amazingly, he was called up for duty again even after having been blacklisted!), the McCarthy era witch hunts, the H-bomb, the Black Panthers, Watergate and the emergence of environmentalism. Thomas Albright, commenting in the San Francisco Chronicle, on Rowe’s work noted “there is a distinctive, moral tone behind all of the diverse things that Rowe does; the notion of the artist as a craftsman in the service of society.” Restored to teaching in 1969, Rowe continued to be a role model for artists, activists and students through his work, his humanity, and his sense of justice.

Richard Correll and Frank Rowe present us with art that serves as a microcosm of the social and political struggles of twentieth century America. Their example is a powerful reminder that great art can serve the social good. Their determination to make that point in their lives and work, as shown in this exhibition, is proof of the strength of the melding of great art and social conscience.

-Art Hazelwood